Everything you need to know about the Principal Agent Problem

The principal-agent problem is a conflict in priorities between a person or entity (the "principal") and the representative (the "agent") authorized to act on their behalf. This problem occurs in scenarios where agents have incentives to act in their own best interests, which are contrary to those of their principals.

The principal–agent problem typically arises when the two parties have asymmetric information (the agent has more information), and the principal cannot directly ensure that the agent is always acting in their (the principal's) best interest.

This problem isn't new.

3,800 years ago, the Code of Hammurabi specified:

“If a builder builds a house and the house collapses and causes the death of the owner of the house—the builder shall be put to death.”

They understood the information asymmetry at play here- the builder knows more about the risks than the client, and can hide sources of fragility to increase profits by cutting corners.

Activities that are useful to the principal are costly to the agent, and it is difficult/ expensive for the principal to track the activities of the agent- in this situation, the agent has leeway on how much effort to exert on behalf of the principal.

"If you want it done, then go. And if not, then send."

What Julius Caesar meant by the above line was that if you need something to be done right, you have to do it yourself. As the principal, you are the owner of the outcome. So you will care, and you will do a good job.

Ownership and control

When a principal hires an agent, they have to give away a certain degree of control over the asset. The agent controls the asset (or project). But the owner owns the outcome. The owner has skin in the game.

Here's the core issue. The person who owns the asset will always care more than the person they hire to manage it.

Those who have the upside are not necessarily those who incur the downside. That's one of the biggest problems with the world today.

Naval believes that incentives are very powerful in influencing human behaviour:

"Almost all human behavior can be explained by incentives. The study of signaling is seeing what people do despite what they say. People are much more honest with their actions than they are with their words. You have to get the incentives right to get people to behave correctly."

For e.g., bankers get performance based bonuses, but do not have to incur any costs for negative performance. This means that they have an incentive to bury risks and, to delay blowups.

Banking & the crash of 2008

The complexity of the banking & financial industry creates an environment fertile for potential incentive conflicts.

Traders generally have unlimited upside on their bonuses, whereas the downside is floored at zero. Any losses are borne by the bank and its shareholders. This perverse incentive bonus system encourage managers to take excessive risks and boost short-term profits.

Traders receive their compensation based on profits created in a given year, regardless of the risk these trades create for the banks in future years.

Under this compensation structure, taking irresponsible risks during a bubble makes perfect sense for an individual trader, even if they know that their actions are likely to contribute to a crash. This is a moral hazard.

For e.g. AIG’s Financial Products division lost ~ $40 billion in 2008 but the team received a total of $220 million in bonuses for that year (> $500,000 per employee).

The bankers were incentivized to lend as much as possible but not to ensure that as much money as possible came back. The people who authorised the subprime mortgages and the derivates did so knowing that they would not have to bear the risk because they were too big to fail- they were working with OPM (Other People's Money).

The government agreed to use taxpayer dollars to bail out financial institutions to avoid a further the financial meltdown.

As Allan H. Meltzer said:

"For some bankers, taking on excessive risk appeared to be a one-way gamble. Either the bank profited and the bonuses increased, or the public took the loss.

If a bank is too big to fail, it is too big."

Everyday examples of the principal-agent problem

Online grocery shopping

Online grocery shopping has gotten popular in developed economies in the last decade. Store employees (agents) have incentives to select items that will expire the soonest, while the customer's (principal's) best interest would be to get the freshest items.

Government

The public (principals) want government officials (agents) to make decisions in the best interests of the common man. In an ideal world, agents would have all the information and act in completely selfless ways to serve the public, even if that conflicted with their individual interests.

In theory, elections would give a reality check to previously elected officials who go against the public interest, and act in their own individual interests.

In reality though, principals have little information about the actions of agents and the implications of these actions.

Election candidates make vague promises, which cannot be measured and reported quantitatively. So it is becomes nearly impossible for principals to identify precisely whether the agents have done a good job or not. Even if it is clear that the agents have failed, it is difficult to point to any particular agent and hold them accountable for the failure.

CEOs and share holders

A company's investors (principals) rely on the CEO (agent) to pursue a strategy that increases stock price or maximizes dividends for shareholders. The CEO could however choose to pay bonuses to the senior management (including themselves).

Subscription based dating website

In this model, a fundamental conflict of interest exists between the users and the company. If the company's (agent's) algorithm does a good enough job and a user (principal) ends up finding a compatible partner in another user- both users are likely to end their subscription which means less money for the company.

Outsourcing/ freelancing

A content marketing agency (agent) may be hired by customer (principal) to create content for their website. But unless the payment is outcome based, the agent might not spend the time necessary to write good content if they could instead create subpar work and get paid the same way.

How can the principal agent problem be solved

When the principal and the agent do not have the same incentives, the result can be a suboptimal decision for the principal.

Principals can attempt to overcome this incentive asymmetry through conditionality (outcome/ performance based payment). But performance is often subjective, and enforcing something like this requires the principal to constantly monitor the agent.

In an ideal world, if the agent has the exact same incentives as the principal (i.e. they are exposed to the same risks), then there would not be an issue. The agent will always behave in the manner that is best for them, and therefore best for the principal. This however, is an aspirational goal.

The question really is, that in the real world when people are tasked with making decisions that have implications for others, how do we ensure that they make the best decisions on behalf of those that they affect? And if there is a risk that the agent might make decisions for their own benefit at the expense of the principal, how do we limit the extent of that risk?

Former US presidential candidate Ralph Nader had proposed that those who vote in favour of war should place themselves or a descendent into military service.

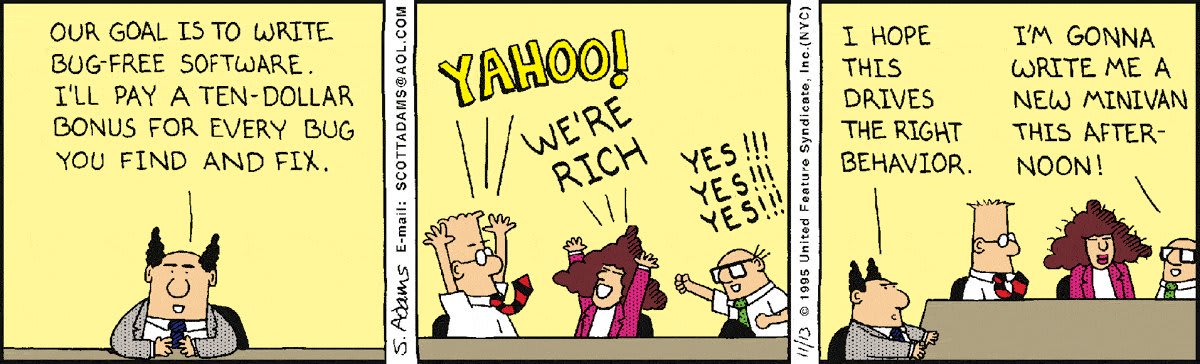

The principal must find a way to incentivize the agent to do what's in the business's best interest.

One of Charlie Munger's favourite examples of the power of incentives is Fedex.

FedEx needed to shift all packages to the appropriate plane in one central location each night to ensure reliable overnight delivery. They tried everything but they had a hard time getting it to work — they were unable to shift all the packages. Then, someone realized that the night shift workers were being paid by the hour. They changed the compensation from an hourly rate to a fixed rate, and everyone could go home when all packages were shifted. The new system worked wonders- incentives were aligned.

In a public company, shareholders could align the incentives of the CEO to their own by tying a significant portion of their compensation to the stock price. Now the CEO (agent) would try to maximize their own compensation, which means they would make decisions that drive the stock price up which is good for the business (and the principals).

In governments, transparency is a good starting point to address principal-agent problems.

As an employee the fastest way to get ahead is to think and act like a principal. Focus on what is best for the business, as opposed to what is best for you. Principals (employers) who see their agents (employees) acting like principals will quickly give them more responsibility, resources, and money.

If you're not thinking like a principal, you're a small cog in a big machine and sooner or later you can be replaced by someone who is willing to have more skin in the game.

If you train yourself how to think and act like a principal, you will eventually become a principal.